The role of age in the desirability of collectibles (Pokemon Cards)

Although I’ve posted this as an article, it isn’t scientific and I have no expertise in philosophy. In fact, there appears to be little research or educational material on this topic, so it would be difficult to create a citation-based article of much substance. This has not been written using AI, though some of the images used are AI-generated. This is a collection of original personal thoughts that explore why and how age contributes to the value of our collectibles. The main purpose of posting this is because it offers perspective. This isn’t meant to be an argument for vintage vs modern or a ‘vintage shill’ thread; just some ideas that might help explain why we love and become so attached to older items in the TCG.

Preface: age is not enough on its own

It’s widely understood that the desirability of collectibles is influenced by a diverse range of factors that work together in different ways, including rarity, popularity, age, originality, condition, the economy, cultural events and social influence. The passage of time, or age, may not confer value to something simply by itself. Not everything that is old is considered valuable; some old coins may be worth no more than several pounds while others may be worth thousands.

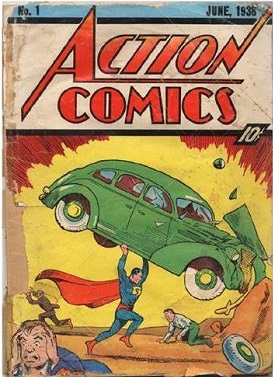

Ancient Celtic coin over 1,000 years old versus a 50p coin from 2009.

The same is true for Pokémon cards. Age becomes significant when it intersects with other external factors related to the era of the object’s creation; it works in collaboration with other things that add value when combined. This might include the method in which something is made being unique to the time, the materials used, cultural phenomena of the era, or the style of the object reflecting the aesthetic preferences of the period. For example, ancient coins minted in period-specific ways, trophies being awarded in specific years for specific events, personal artefacts owned by people of significance, or in our case, trading cards being tied to a culturally iconic franchise. The more desirable the collectible, the more it tends to embody these contextual elements.

What value does age contribute by itself?

One perspective is that age adds value simply by being a catalyst for change. Time passing can bring a sense of finality to an era, and also facilitates changes in how people value the things around them. As people themselves age, they often develop perspectives and insights not yet grasped by younger generations. This includes appreciating the transient nature of creative manufacturing. As time passes, most collectibles will at some point cease production entirely. Coins stop being minted, art stops being painted, jewellery stops being crafted, and Pokémon Cards stop being printed. This may happen for various reasons; changes in broader consumer demand, adapting a brand to newer audiences, financial inviability, or simply going out of style. Whichever the reason, it leads to a limitation in accessibility, which in turn leads to a sense of scarcity.

Still: age and limitation do not by themselves create value sufficient for something to be considered desirable; they must work together with other appealing characteristics like those described earlier. It’s probably not unreasonable to suggest there’s not a huge amount of demand for a ‘1 of 1’ rusty nail from an 1850s train track.

The passage of time is the catalyst for historic value

Ancient tribal totems, Egyptian Canopic jars and Confederate gold are examples of artifacts that many consider to have historic value. The passage of time has allowed many events - both associated and unassociated - with these items to take place that have completely reshaped the world around them. The items themselves remain, for the most part, physically unchanged. Despite time passing, they remain a steadfast physical reminder of a past, celebrated culture.

As eyebrow-raising as it might be to suggest after talking about Canopic jars, Pokemon Cards could be considered a modern example of a physical, tangible manifestation of celebrated culture. The further time steps forward, the further this is cemented into commercial history. A collectible or an artifact produced at any given moment will inherently capture the zeitgeist, or ‘feeling’, of the time. There will forever be some aspect of society or culture associated with that item. This is of course a key component of nostalgia, which as we all know is another significant driver of our desire to collect specific things.

Physical signs of age

Historically, the older that items [that are considered collectables] became, the more wear and tear they accumulated. Old items that are in better condition are usually considered more valuable than their poor-condition counterparts.

In Western culture, we typically celebrate the preservation of the aesthetics, beauty or physical perfection of both living and inanimate objects. There is a display of effort, patience and appreciation that becomes attached to an object when it has been cared for and preserved for many years. In an abstract sense, the object itself has captured the ‘energy’ from the emotional care that has been given to it to maintain its aesthetic. This prolonged investment of energy translates to an increase in its perceived value.

The older the object becomes, the more of this emotional energy it captures. Therefore, it would follow that the older the item and the better its condition, the greater the reflection of the invested emotional energy, and the greater its inherent value to people who can understand and appreciate that value. This is one of the many ways in which people become connected through collectables; an appreciation firstly of what the object itself represents, followed by an appreciation of the scalable emotional energy another person has invested in that object.

Cultural differences

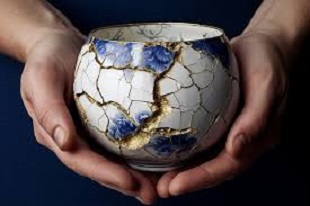

The desire to own old collectables, specifically those that are in top condition, appears to be deeply-embedded in our psychology. However, not all cultures and philosophies conform to this perspective, and some people derive the philosophy of their physical environment from a completely opposing viewpoint. Although not specifically relating to collectibles, views on the value of condition through age are presented in a much different way in Wabi-Sabi, for example.

In Japanese culture, Wabi-sabi is the Art of Impermanence. One aspect of this philosophy is a celebration of beauty that can be found through the transience of perfection, and the physical manifestations of aging. Signs of age in items such as heirlooms or pieces of historic importance are preserved rather than corrected. They are left this way in order to fulfill the idea of finding pleasure in things that reflect the notion that nothing lasts.

Age is celebrated by preserving its physical marks; their continuation tells a story of the utility the object has served over time, and the role it has played in the lives of, potentially, multiple generations of people. Suffice to say there is little demand for grading companies within cultures that subscribe to this philosophy.

Tangibility: the renewed craving to hold history in our hands

It’s clear that we cannot have history without age (that is, the passing of time). We’ve established that some physical objects have an innate, passive ability to capture history from their era, carry this with them through time, and then reflect it outwardly.

The 21st century has since propelled us into a digital epoch, further away from a world in which we interacted in a more physical way. We have fewer hand-to-hand exchanges, little need for hard cash or coins, CD music libraries are near extinct, we have cameras that require no film and the ability to store a million books on a device smaller than just one.

More recently, there are signs that we have again begun to crave ownership of tangible things, perhaps in some way reflecting a primal human need for physical interaction with items we perceive to hold value. That value might be monetary, nostalgic, historic, or a combination of those and many others. Vinyl LP purchases have risen for the 16th consecutive year in the UK in 2023, by 2023, the Pokemon Company printed more than double the total cards produced worldwide by 2016, in 2022 the global board game market was worth around $19 billion, and within the next 5 years it’s expected to reach almost $40 billion.Through this, we create heirlooms; a seemingly bygone family tradition that cannot be adequately recreated using digital media. Entering a highly digital age has allowed people to lose touch, in both a literal and metaphysical sense, with tangible experiences.

Age facilitates history, history carries value, history can be captured within physical objects, and those objects can confer that value to us. People enjoy the spiritual value of interacting with history through a physical medium. As limited and flawed animals, we generally struggle to conceptualise periods of time beyond 100 years. The ability to interact with something that is hundreds or thousands of years old is a physical connection to the past, and has the ability to ignite the realisation that these world-defining events truly took place and left behind their mementos.

In our current world, particularly this niche space we occupy in collecting trading cards, we will gladly queue to get our copies of the latest promo card from the Pokemon Center, or attend events at the local regional TCG tournament, or bargain with the local Japanese post office for a chance at getting hold of one of their last Stamp Boxes. As time passes and both we and our cards age, the experiences we went through to build our collections attach value to them. The places visited and the people we met attach value to them, and that value will be carried by time to eventually be dispensed again to either us, or the next collector. Without the passage of time, this value cannot be built.